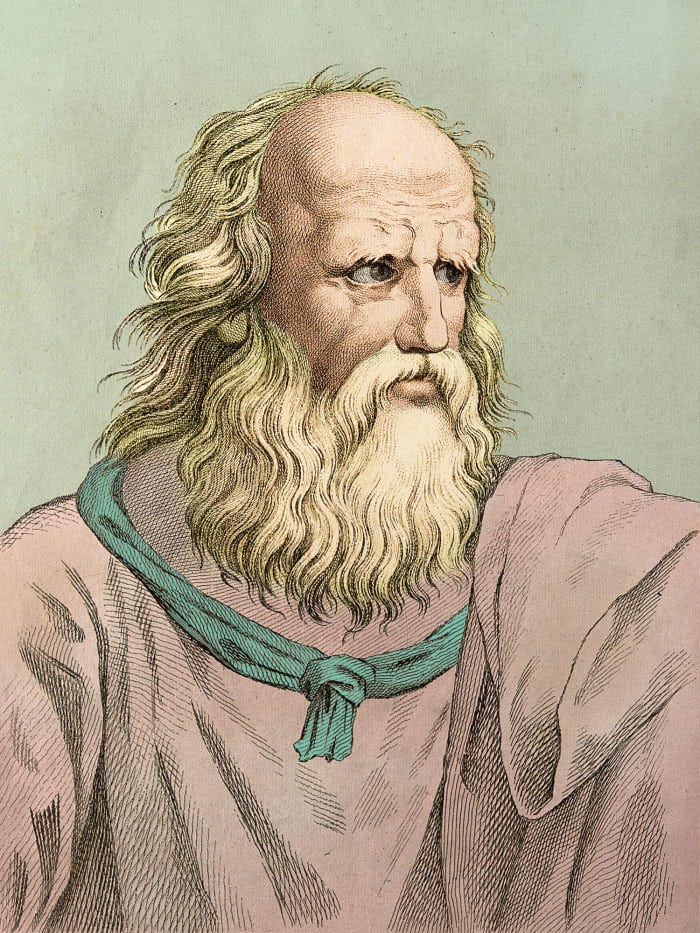

So, that Plato guy.

You’ve heard of him, of course. Famous philosopher, Greek, debater, foundational figure in western philosophy and thought, etc.

Also - pugilist?

I may the only one who DOESN’T know the story of how Plato got his name. Now, bear in mind - we’re talking someone who lived a few-odd millennia ago, so these stories are a bit dim in passing. And there’s a language issue, as well; even in English, “Rose” is a name - but it doesn’t mean that Rose will be an award-winning gardener. She might be a data analyst and Python expert, and have a track record of brutally murdering every plant she’s ever touched.

Point being, add “normal” name issues to the ancient Greek language, and then throw in a dash of a few dozen centuries, and there’s some definite uncertainty here.

That said, Plato’s name appears to hold a great story locked away.

The Story

Plato wasn’t born “Plato.” His given name was Aristocles. But after training as a wrestler, he was given the name Plato - which, broadly, means just that - “broad.”

Now, a bit of research shows that some people think the “broad” referred to his head, or possibly his intellect. We might say something similar when we refer to someone as having a strong mind.

But there’s good evidence to show that Plato did train as a wrestler, and that he was apparently skilled enough at that discipline to compete at the Isthmian Games, a distant precursor to the Olympics. That being the case, the conclusion might be that “broad” could be more equivalent to “broad-shouldered.”

Or, as we might say, that Aristocles guy was jacked.

There’s some added evidence from Plato himself, with his references to physical exercise.

The Laws

It’s a worth a closer look at one of the more famous of those references, an extended section from the dialogues that form Book VII of The Laws. Like many Greek works, The Laws is a conversation between two (or sometimes more) men. In this case, the subject under discussion is the proper formation of the laws and rules of a city-state; hence the title of the work.

One of the key passages runs thus:

Education has two branches—gymnastic, which is concerned with the body; and music, which improves the soul. And gymnastic has two parts, dancing and wrestling. Of dancing one kind imitates musical recitation and aims at stateliness and freedom; another kind is concerned with the training of the body, and produces health, agility, and beauty. There is no military use in the complex systems of wrestling which pass under the names of Antaeus and Cercyon, or in the tricks of boxing, which are attributed to Amycus and Epeius; but good wrestling and the habit of extricating the neck, hands, and sides, should be diligently learnt and taught.

This is the argument Plato develops throughout Book VIII; how should education and physical education be conducted? Note that Plato isn’t as concerned with the lower classes; the focus of his work is on legislators - the ones writing the laws, as well as the laws themselves.

Why Exercise?

Plato varies a bit in his application of gymnastics, including wrestling and boxing. As mentioned above, the primary focus is clearly warlike. At one point, he’ll even state:

Of dancing and gymnastics something has been said already. We include under the latter military exercises, the various uses of arms, all that relates to horsemanship, and military evolutions and tactics. There should be public teachers of both arts, paid by the state, and women as well as men should be trained in them. The maidens should learn the armed dance, and the grown-up women be practised in drill and the use of arms, if only in case of extremity, when the men are gone out to battle, and they are left to guard their families.

At the same point, he also speaks at length of the value of moderation, and views physical exercise as key to pushing back against twin evils of indulgence and the love of money (that’d be worth a separate post in itself).

Dancing Around The Ring

But what I found most intriguing was Plato’s description of the “dancing” element of gymnastics. Clearly, this could be something musical - but The Athenian, the primary speaker in the dialogues, has already dealt with music as a separate category.

There’s a great clue as to what Plato actually means by dancing, buried in Book VII:

Wrestling is to be pursued as a military exercise, but the meaning of this, and the nature of the art, can only be explained when action is combined with words. Next follows dancing, which is of two kinds; imitative, first, of the serious and beautiful; and, secondly, of the ludicrous and grotesque. The first kind may be further divided into the dance of war and the dance of peace. The former is called the Pyrrhic; in this the movements of attack and defence are imitated in a direct and manly style, which indicates strength and sufficiency of body and mind.

Later, Plato’s descriptions of “dances of peace” sound like, well, dancing; he considers it entirely pertinent for men to learn dances of peace, as in them a man “learns to bear himself gracefully and like a gentleman.”

But what about those Pyrrhic dances, with the imitation of movements of attack and defence? In these “a man imitates all sorts of blows and the hurling of weapons and the avoiding of them.”

Here we have something that we might call today “martial arts,” dancing (movement) that imitates various armed or unarmed combat.

Or barring that, something like good old boxing and wrestling.

Pugilism, Plato, and Me

Let’s circle back around.

Plato may or may not have earned his nickname as a more-than-halfway decent wrestler; he certainly valued physical, competitive exercise, both as necessary to a well-run state and critical for personal moderation.

And he found some of it to border on art, in which actions and words met in a beautiful form.

I’ve got some limited first-hand experience, here. I’ve dabbled in a lot of different forms of physical exercise over the years - the gym, various team sports (Ultimate frisbee!), Tai Chi, fencing, running, Taekwondo, running again - but recently found myself craving something more combative.

I’m back in the gym, and the dirty, dark, dingy gym that passes for Dumbarton’s finest boasts a no-frills boxing club. A couple times a week, wee Billy runs us ragged with cardio, circuit training, and then a dozen or so rounds hitting the bags. It’s sweaty, sweary (I live in Scotland, after all, where the f-word is an interjection) and absolutely brilliant.

I doubt I’ll ever attain to the level of dancing around the ring. But I can hope that my words and actions can be in tandem; I can be a fit man of God who strives to keep both body and soul in shape to serve Him.

Action Points

Don’t neglect physical discipline. A sound mind, in a sound body, builds moderation, discipline, mental fortitude - basically, you can’t go wrong.

When in doubt, hit something. Nothing beats the simple feeling of pounding something with your fists.

Remember, physical exercise won’t save you. The mental always wins, so keep your mind sharp. I find that exercise sharpens the mind; I wouldn’t want to go so far that the pendulum swings back the other way.